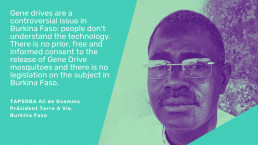

Interview with Ali Tapsoba

Gene drive technology carries high risks. Yet it is being promoted by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as a solution to malaria. On the occasion of World Malaria Day, the Stop Gene Drives campaign is launching a project that presents different perspectives on how to combat malaria.

Ali Tapsoba de Goamma is a human rights activist and spokesman for an alliance in Burkina Faso against the release of Gene Drive mosquitoes in his home country. In this interview with him we wanted to know which malaria control measures have benn implemented in his country so far. We also ask for his perception on the attitude of the local population towards the planned field trials with Gene Drive mosquitoes.

Mr. Tapsoba, which measures have been applied to stop Malaria in Burkina Faso? Which were successful, which not? Which have not yet been attempted? Which additional measures would be needed in Burkina Faso to end the suffering from Malaria?

Despite government efforts, malaria remains the leading cause of medical visits, hospital stays and deaths in Burkina Faso. Beyond loss of life, malaria also impacts the economy, hampers productivity, and places a significant burden on the health system.

However, the lethality rate of malaria has dropped significantly since 2015 to less than 1%.

The main vectors for transmission of the disease are the mosquito species Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus.

Possible measures to combat malaria in Burkina Faso:

- Distribution campaign called MILDA, which included impregnated mosquito nets with long duration of action (MILDA =Moustiquaires Imprégnées d’Insecticide à Longue Durée d’Action, insecticide)

- Use of repellents indoors and on clothing.

- Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with oral medication of amodiaquine (TPI, Traitement Préventif Intermittent du paludisme) and seasonal malaria chemoprevention (CPS, Chimioprévention du Paludisme Saisonnier). The antimalarial drugs sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and amodiaquine are administered to prevent infection.

- Hygiene measures: construction of sewerage systems, cleaning of gutters, modification of water storage methods.

- Larval control

- Indoor spraying with insecticides.

- Distribution of routine mosquito nets to pregnant women and children under one year of age,

- Strengthening prevention for pregnant women.

Of these methods, the MILDA distribution campaign, the use of repellents, and the preventive treatment methods are working well so far.

The measures to improve hygiene conditions, indoor spraying with insecticides, and larval control have been implemented to a lesser extent. However, these three measures as well as the use of medicinal plants in preventive and curative treatment as well as educational measures for behavioral change should be addressed more intensively.

How is the use of Gene Drive technology discussed in your country as compared to other measures to combat malaria? Does the local population understand how the technology works? Do they agree to testing/using this technology?

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are discussed controversially in Burkina Faso. For example, scientists and consumers have rejected genetically modified cotton.

Gene drives that are not yet in use are a contentious issue. A report by Target Malaria on the release of 6400 genetically modified mosquitoes in July 2019 states that the goal was not to fight malaria, but to test how long these mosquitoes live, how capable they are of adapting to the natural environment, and how they spread.

The citizens of Burkina Faso categorically oppose the future use of this technology. The resistance has made it possible to block a release in 2020. And we will continue to prevent a release. Local people in Burkina Faso know nothing about Gene Drives. Even the scientific community has difficulty understanding this technology. There is no free, prior and informed consent for the release of Gene Drives and there is no legislation on this issue in Burkina Faso.

In conclusion, malaria has become a business model in Africa. It is a health mafia that benefits the pharmaceutical industry and some governments. I strongly doubt the statistics published by the health authorities. To fight malaria in Africa, it is enough to develop a good policy of sanitation, create a plan for the ecological design of cities and villages, preserve ecosystems and biodiversity, increase literacy rates, and ensure virtuous governance in the states.

—

Further interviews have been conducted with:

Andreas Wulf of Medico International, officer in the Berlin office for global health issues, who gives us information about the role of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in international health policy and presents his view on necessary conditions for the implementation of the human right to health in Africa.

Click here for the interview

Pamela J. Weathers, professor and researcher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, USA, on the efficacy and controversial safety of Artemisia tea infusions for treating or preventing malaria.

Click here for the interview

—

References provided by Mr. Tapsoba:

- World Health Organisation (2019). World Malaria Report 2019 World Health Organisation (2019).

- USAID President’s Malaria Initiative FY 2019 Burkina Faso Malaria Operational Plan

- USAID 2017: Financing of Universal Health Coverage and Family Planning – A Multi-Regional Landscape Study and Analysis of Select West African Countries: Burkina Faso

- Universal Health Partnership coverage (2019). http://uhcpartnership.net/country-profile/burkina-faso/(le lien est externe)(link is external)

- L’Économiste du Faso 2016

- https://www.la-croix.com/Sciences-et-ethique/Le-paludisme-lautre-epidemie-devastatrice-2020-07-17-1201105379

- https://www.jeuneafrique.com/654776/societe/burkina-controverse-autour-de-moustiques-ogm-contre-le-paludisme/

- https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2018/06/29/des-moustiques-ogm-contre-le-paludisme-le-projet-qui-fait-debat-au-burkina_5323380_3212.html