Day: April 25, 2022

Interview with Dr. Sory

Gene Drives will most probably be released first to fight malaria. We therefore created this series of interviews with health care experts, researchers and civil society to amplify their voices and concerns around this technology.

How did you get involved with Gene Drives as a burkinabé epidemiologist?

Dr. Sory is an epidemiologist with 10 years of experience. Among others he has been the director of quality of the biggest hospital in Burkina Faso from 2016-2018, the focal point for non-transmittable diseases, member of the COVID 19 epidemic response unit and part of the Atlanta Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

His focus has always been on the big questions around public health. He got involved with Gene Drives when he headed a group of civil societies raising questions about the research conducted by Target Malaria. He eventually dropped out when the Regional Director of the Bobo Dioulasso Health Science Research Institute informed them about the release of genetically engineered mosquitoes on a too short notice. Seen that this did not give them any chance to react, he decided to leave the organization so as to not raise the impression that his group was consulted and agreed on that - seen that this was not the case at all. His main concerns back then and still nowadays around gene drive mosquitoes are that it is an untested technology whose indirect or direct impacts on human health and the environmental equilibrium cannot be predicted. He was never categorically against the release of gene drive mosquitoes, but asked for a transparent and precautionary step-by-step approach in order to properly assess all impacts.

How is the situation in Burkina Faso and what needs to be done?

Dr. Sory is positive about the existing malaria strategies in his country and the existing and upcoming measures to fight the disease.

Key to the success of the strategies is access to information, education and a change in behavior. There are strategies in Burkina Faso that are targeted towards children between 3 and 5 or pregnant women, but hygiene and sanitation remains a big problem. The upcoming vaccines seem promising to him and could be a valuable addition to the existing strategies. Furthermore, research on the efficacy and use of the artemisia plant could open new doors. Drugs are accessible in Burkina Faso and the government is subsidizing it for children under 5 and pregnant women.

What steps and approaches are needed?

A further game changer in the fight against malaria would be to involve sectors and ministries that are not dealing with health care, because malaria affects everything and in return is affected by malaria. Housing, education, agricultural practices, city planning, drainage systems, all these sectors should be involved in a holistique solution against malaria. The biggest obstacle for the disease still remains the “environmental hygiene” as Dr. Sory calls it. Everywhere the water stagnates, being it during rain or dry season. The grey water of households is flushed in the streets, there is no proper drainage system so water stagnates everywhere, which is the breeding ground for mosquitoes. When it rains the water remains literally everywhere. “We can invest billions of dollars in other measures, but if we do not resolve this issues, we won’t fight malaria.”, concludes Dr. Sory. This approach would also help in the fight against other diseases, seeing that other main mortality causes, such as diarrhea or lung diseases, result from low hygiene and sanitation standards.

What do you think about Gene Drives to fight malaria?

In regard to Gene drives Dr. Sory believes that there is not much incentive to approve a technology that affects the very basis of organisms when we cannot measure its impact, especially if there are already other solutions at hand that we could increase and support.

--

These are the interviews on the topic held so far with the following experts:

Andreas Wulf, physician and expert for global health policy at Medico International in the Berlin office, provides his views on the role of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in international health policy and his outlook on necessary conditions for the implementation of the human right to health in Africa.

Click here for the interview

Ali Tapsoba de Goamma, human rights activist, and spokesman for an alliance in Burkina Faso against the release of Gene Drive mosquitoes in his home country, on the malaria control measures implemented so far and the attitude of the local population towards the planned field trials with Gene Drive mosquitoes.

Click here for the interview

Pamela J. Weathers, professor and researcher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, USA, on the efficacy and controversial safety of Artemisia tea infusions for treating or preventing malaria.

Click here for the interview

Lucile Cornet-Vernet, founder of La Maison de L’Artémisia, and Arnaud Nouvion describe the potential benefits of the Artémisia plant and state that more funding is needed to conduct clinical studies, proving once and for all that the plant is a great tool in the fight against malaria.

Click here and here for the interviews

More interviews to follow.

Interview with Lucile Cornet-Vernet

Gene Drives will most probably be released first to fight malaria. We therefore created this series of interviews with health care experts, researchers and civil society to amplify their voices and concerns around this technology.

How did you get to work on malaria and what are you doing?

Lucile Cornet-Vernet is the founder of “La Maison de l'Artemisia” (engl.: the house of artemisia) founded in 2012. After her friend, Alexandre Poussin, got severly sick from Malaria in Ethiopia and recovered due to a tea made from the artemisia plant she started on a one year research adventure, where she read through all the publications around artemisia and malaria, back then around 800, nowadays approximately 1500. She called doctors who worked with the plant and created a whole bibliography on the state of the art around artemisia curing malaria. She then decided to dedicate her entire work to that plant and created the first “Maison de l’Artémisia”, nowadays there are around 105 of them in 27 countries. They function as research and training centers, where especially vulnerable populations (low income or remote communities) get formations on how to grow, harvest and prepare the preventive or curative teas.

What plants are you working with and what about emerging resistances to Artemisinin?

Before they achieved this, Lucile reached out to an agronomist and they worked on adapting the seeds that originally came from the high plateaus of China to the African regions. Artemisia has a high genetic diversity. Lucile managed well to adapt the seeds to different climates.

Lucile works with two different plant varieties. The Artemisia afra and Artemisia annua. The second comes from China and has 23 different components against malaria. The first one is a bit less researched but has at least 10 components, contains no artemisinin and is a perennial bush, making it much easier for people to grow and sustain it. There has been some research published about the emergence of artemisinin resistance in south-east Asia. This does not threaten her project, says Lucile, seeing that artemisinin is only one component in the plant that fights the disease and that Artemisia afra for example does not even use that. Furthermore, this resistance has been observed for quite some time. Whereas in China, where Artemisia annua originally comes from and where the plant has been used over centuries (and is officially malaria-free since 2021) no resistance has been detected. Lucile furthermore describes the plants as “poli-therapeutical” due to their multiple anti-malarial components. That is more diverse than any drug on the market and makes it resistant to resistances.

Why isn't the plant the mainstream solution to malaria then?

The biggest obstacle to her work is that they lack funding to do large scale clinical tests with the plants, conducted by uncontestable doctors, so that the plant could be mainstreamed as a solution. Lucile has initiated a consortium with a dozen world-renowned research organizations, such as Institut Pasteur. This consortium evaluates the efficacy of artemisia and would conduct randomized tests, when funding comes in.

What makes malaria worse than most other diseases?

Lucile talks about the alarming effect malaria has on the whole continent. Apart from thousands of deaths that mostly hit the poorest, pregnant women and children, the disease creates a vicious cycle of poverty. Malaria can weaken people for a long time, which prevents farmers from sowing their seeds at the right point in time, mothers from selling their surplus on markets to generate an income or children from going to school. The world has set its mind on producing very cheap medicine against malaria, but families still have to afford the treatment, which in many cases is even wrongly produced and does not cure the people.

Lucile gives the example of the DRC, where 60% of the budget from the health ministry is spent on malaria control, keeping the country trapped.

What do you think about Gene Drives?

Regarding gene drives, Lucile does not see them as a solution. She has a quite clear stance against GMOs. She managed to adapt the Artemisia seeds to a whole continent, with different climates and ecosystems, without knocking in a gene for heat resistance. “Before doing something complicated, why not do it easy?” We can’t know what the effects of GDOs are, therefore she’d propose to rather work on the solutions we have at hand. Like the artemisia plant, that would give back the power to the people to treat themselves. The solution is effective, cheap, with a low carbon footprint and local.

____

Further videos: https://youtu.be/xI_dKFhojhM

The book published by Lucile: Artemisia | Actes Sud (actes-sud.fr)

--

These are the interviews on the topic held so far with the following experts:

Andreas Wulf, physician and expert for global health policy at Medico International in the Berlin office, provides his views on the role of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in international health policy and his outlook on necessary conditions for the implementation of the human right to health in Africa.

Click here for the interview

Ali Tapsoba de Goamma, human rights activist, and spokesman for an alliance in Burkina Faso against the release of Gene Drive mosquitoes in his home country, on the malaria control measures implemented so far and the attitude of the local population towards the planned field trials with Gene Drive mosquitoes.

Click here for the interview

Pamela J. Weathers, professor and researcher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, USA, on the efficacy and controversial safety of Artemisia tea infusions for treating or preventing malaria.

Click here for the interview

Arnaud Nouvion, consultant La Maison de L’Artémisia, describes the potential benefits of the Artémisia plant and state that more funding is needed to conduct clinical studies, proving once and for all that the plant is a great tool in the fight against malaria.

Click here for the interview

More interviews to follow.

Interview with Arnaud Nouvion

Gene Drives will most probably be released first to fight malaria. We therefore created this series of interviews with health care experts, researchers and civil society to amplify their voices and concerns around this technology.

How is the financial situation around Malaria?

“It is great how much money is available these days to fight diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis or aids. The Global Fund has recently raised 14 billion dollars, from which a big chunk is dedicated to malaria. Most of the money is spent on nets, the newest medicine and the vaccin.”, says Arnaud Nouvion from the Maison de l’Artémisia (engl.: house of artemisia),

“I think that is great! Every money spent to fight malaria is well spent.”

What "solutions" are you working on?

He points out that there are also cheaper measures against the disease, such as the artemisia plant, that would “only” require 10 million dollars to proceed with clinical studies and prove once and for all if the plant works. This money would be needed to fulfill the requirements of the World Health Organization. There are a lot of renowned doctors and research institutes, such as l’Institut Pasteur or the University of Tübingen, that have joined forces in an international consortium to examine the benefits of the artemisia plant. But they still lack the funding to conduct their research. For pharmaceutical labs there is no incentive to work on the plant, because the main idea is that the plant would be easily available and cheap. Economically speaking it makes sense that no for-profit-company works on this. Labs are made to develop highly complicated medication and artemisia is not.

“Artemisia is the “praise of simplicity”, says Arnaud, “You simply boil a handful of the stem and the leaves for 10 minutes and you get your tea.”

This has been practiced in China for centuries. The nobel prize laureate Tu Youyou discovered in traditional medical books that artemisinin (an extract from the artemisia plant) could cure malaria.

Why have no philanthropists invested in that?

Arnaud Nouvion believes that this solution has not reached the philanthropes yet. Because if they’d discover that, it would be a “dream come true'' for them. This could have the biggest impact. It could save thousands of lives. Malaria is not the deadliest of the diseases, but it has the worst impact on the livelihoods of people. Nowadays there are thousands of hectares all over Africa where Artemisia is grown, in backyard gardens, by big companies or by farmers cooperatives. All are good, all work. “We have indications that it works, we just need the clinical studies to prove it once and for all and then maybe philanthropists might see it too.”, says Arnaud Nouvion, “when it comes to the correct dosing of artemisia, here again science would do its job. More research will lead to better treatment.”

He furthermore points out that Artemisia afra does not contain artemisinin, but does work against malaria, thereby even further decreasing the risk of creating resistances.

What do you think about Gene Drives?

Arnaud talks about Malaria as a really big wound, a blight, affecting many people. He sees a hierarchy of solutions. When comparing artemisia to gene drives it seems quite clear to him. On one hand he thinks, we have a cheap and easy solution that has been tested for hundreds of years and on the other hand we have an expensive, complicated and untested approach. He makes clear that he is not against novel solutions or that no money should be spent on research diversification, but that in this case the answer to the question: “which measure should be used first?”, is quite clear.

And what about the vaccine?

A vaccine against malaria would be great too. At the same time some obstacles have to be overcome, such as keeping the refrigeration chain up until the very remote areas and guaranteeing that children between zero and two years get four doses. When it comes to artemisia Arnaud is precautious in advising it for babies. Here again he points to the lack of clinical studies. He simply doesn’t know how it would affect babies, therefore he takes a precautionary approach and advises it only for older children.

La maison de l’Afrique will be hosting a webinar on the 25th that is also under the umbrella of “the praise of simplicity”. Three different approaches to fighting malaria will be presented. One speaker will talk about the use of artemisia, the other one about a repellent to be applied on the skin and the last one will present a trap to be placed around the house with an ecological insecticide. Three further “users” of these measures will talk about their experiences with it.

A mug of artemisia tea every morning during the rainy season and nobody dies from malaria anymore. Sounds too easy? Maybe we should try this first before using complicated and expensive approaches such as Gene drives?

--

These are the interviews on the topic held so far with the following experts:

Andreas Wulf, physician and expert for global health policy at Medico International in the Berlin office, provides his views on the role of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in international health policy and his outlook on necessary conditions for the implementation of the human right to health in Africa.

Click here for the interview

Ali Tapsoba de Goamma, human rights activist, and spokesman for an alliance in Burkina Faso against the release of Gene Drive mosquitoes in his home country, on the malaria control measures implemented so far and the attitude of the local population towards the planned field trials with Gene Drive mosquitoes.

Click here for the interview

Pamela J. Weathers, professor and researcher at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, USA, on the efficacy and controversial safety of Artemisia tea infusions for treating or preventing malaria.

Click here for the interview

Lucile Cornet-Vernet, founder of La Maison de L’Artémisia, describes the potential benefits of the Artémisia plant and state that more funding is needed to conduct clinical studies, proving once and for all that the plant is a great tool in the fight against malaria.

Click here for the interview

More interviews to follow.

World Malaria Day 2022

What risks are we willing to take to (maybe) end malaria?

25.04.22 – After a tremendous decrease in malaria cases in the last two decades, malaria is on the rise again, having killed 677.000 people in 2020, among them 80% children under 5. Apart from being deadly, malaria is detrimental for the livelihoods of entire families, communities and countries: farmers not being able to sow their seeds on time, mothers not being able to sell surpluses on markets to earn a living or children not being able to go to school and benefit from education – a vicious cycle of poverty. While this disease affects one third of the world’s population, some scientists suggest that a new technology called gene drive could be a game-changer.

Gene Drives – manipulating the DNA of mosquitoes to pass down an extinction gene

The research consortium Target Malaria, mostly funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Open Philanthropy Fund, is developing genetically engineered mosquitoes in the lab that would either make all offspring male or all female offspring infertile. They use the Crispr-Cas methodology to implant a system into their DNA that would replicate when mosquitoes mate, ensuring that this gene spreads throughout the wild mosquito population. But while some hope that this would be the magic bullet to suppress mosquitoe populations and stop the malaria transmission cycle, this currently unproven high risk technology poses fundamental questions for humanity: How far are we willing to go, how high can the risks and uncertainties be in order to test a hypothesis?

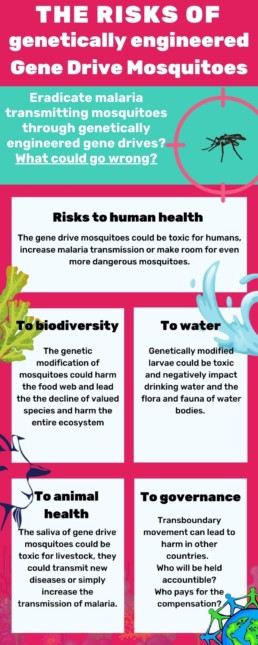

The Risks of Gene Drive mosquitoes

The risks and consequences of genetic engineering are very hard to predict, especially when the organism is supposed to live and mate in the wild. This is because genes do not only affect the physical shape of animals but also their behavior, their interactions with other species and the way bacteria and parasites affect them. A suppression/eradication gene drive is going to have repercussions along the entire food web and would likely mean that their ecological niche will be occupied by another species, and that the plasmodium parasite (which causes malaria) would lack a host – with unknown consequences. In addition, there is a risk that the modified genes could be passed from the mosquitoes via ‘horizontal gene transfer’ to other species and suppress their population too. If this would affect so called “valued species”, the ecosystems could collapse or be severely damaged.

At this point in research scientists do not know if the genes might be toxic for humans or create allergic reactions. Furthermore, the expected change in behavior of the mosquitoes could lead to increased biting and/or even increased malaria transmission. Also, if humans eat animals that ate the gene drive mosquitoes before they could suffer from secondary toxic effects. Last but not least, if the anopheles gambiae mosquito is eradicated, potentially another mosquito could take its spot, increasing the burden of other diseases.

Same as for humans, gene drive mosquitoes could be toxic for livestock, transmit new diseases or may even – counter-intuitively – increase the transmission of malaria.

Mosquito larvae play an important role in water bodies. Genetically modified larvae could be toxic and negatively impact drinking water and the flora and fauna of water bodies.

As this technology is still very new, naturally studies and discussions on their risks, possible adverse consequences as well as the type of global governance and international regulation needed are only in their infancy. For example, guidance materials for risk assessment have not even been commissioned by the global community. In addition – a plethora of important political, socio-economic, cultural and ethical questions remain unaddressed and unanswered. For example, who should be included in the decision making process and who should be consulted before any release? Would it be enough that a national government such as the Burkinabe government allows such a release and that local village chiefs give their consent? How would decision-making processes be designed to uphold the internationally enshrined rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities to say no to projects that could affect them and their territories? Who would be held responsible and who would have to pay for compensation if the gene drive mosquitoes crossed borders and had adverse impacts on ecosystems or farming in non-target environments?

At the same time there are measures at hand that have in the past been used to end malaria in countries such as, most recently, China and El Salvador, being officially declared malaria free in 2021, preceded by Algeria and Argentina in 2019.

What have been the most successful tools to fight malaria?

Research suggests that the number one tool for the decrease of malaria since 2000 are insecticide-treated bed nets. Approximately 65% of the progress achieved between 2000 and 2015 result from the use of these nets.

Poor Water and Sanitation conditions are associated with a number of diseases, among others with the occurrence of malaria. A better sanitation situation would be a holistic approach to fight malaria, while also fighting diarrhea and respiratory infections that kill millions of children every year. Further research shows that good sanitation and piped water are associated with a lower prevalence of malaria among the population. Dr. Sory shares this opinion and believes that correct drainage systems would heavily lower the burden of malaria.

Artemisinin was rediscovered by the Nobel Prize laureate Tu Youyou who found the cure for malaria in traditional books. It is a component from the Artemisia plant. Drugs against Malaria now often contain artemisinin and can cure all malaria strains present nowadays. Initial research suggests that a tea prepared with the Artemisia plant can have preventive and curative effects. It seems that another plant of the Artemisia family, Artemisia afra, could have similar effects, without containing artemisinin. Lucile Cornet-Vernet and Arnaud Nouvion said that more clinical studies are needed to prove once and for all that these plants work. Until now the WHO asks to not use the plant as tea to not cause resistance to artemisinin. Resistances to artemisinin have been discovered in South-East Asia, but not in Africa so far. Lucile Cornet-Vernet on the other hand points to the fact that in China, this plant has been used for about 2000 years and no resistance has been discovered there yet. Furthermore, the plant comes with a variety of components that could potentially cure malaria, thereby being a “poly-therapy”. Access to health care providers diagnosing malaria and prescribing the drug and the financial means to afford them are the limiting factor here. Or else access to seeds or the Artemisia leaves to cure oneself could be useful, if clinical studies can be conducted and no link to the creation of resistance can be drawn.

There is a multitude of repellents that can protect humans between 3-10 hours from mosquito bites. Seen that most mosquitoes bite in the evening/night, this protection is very helpful when going out late. Many of them have chemical ingredients and some have plant-based ingredients. Amongst those, the German society for tropical medicine, travel medicine and global health recommends only the ones with oil from the lemon eucalyptus and points out that for the other natural repellents too little studies have been conducted. This could be a path worth exploring.

Early detection helps people first to get the needed medicine as soon as possible, suffer the least impact of the disease, and second it helps to decrease the risk of a local outbreak in a community.

A new vaccine was recently approved by the WHO for children under 5 years old. A pilot phase was concluded in Ghana, Malawi and Kenya. Employed prior to high transmission periods of malaria this vaccine seems to have positive affects on immunization. It is recommended that children above 5 months get four doses of the vaccine. Over a 4 years follow-up the efficacy of the vaccine against malaria was 36%.

Why is there still malaria in the world then?

To fight malaria the whole toolbox of measures (as mentioned above) needs to be employed, ranging from prevention through nets and repellents, to access to rapid tests to break the infection chain and access to medicine a few hours after being bitten to cure humans. Adding to this; a holistic approach, including urban planning, education, drainage systems and access to health care is needed to fight malaria – as well as many other diseases that trap people in poverty and create a vicious cycle.

What is the Stop Gene Drives Campaign asking for?

In light of the huge variety of to date unassessed possible environmental, health and socio-economic hazards, the potential for economic and political conflict and a plethora of social, ethical and cultural caveats that the environmental use of gene drive technology would entail , the Stop Gene Drive Campaign demands a global moratorium on the release of gene drive organisms. This means that no gene drive organism should be allowed to be released into the environment – not even for field trials – unless a range of conditions have been fulfilled. Read our policy recommendations here.

It seems to us that malaria prevention funds should be directed at strengthening local health care systems, sanitation and education to turn the fight against malaria into an intersectional approach to fight poverty and neglected diseases in general.

__________

Further readings:

Read more about possible gene drive applications here

Read our FAQ about gene drives here

Read more about gene drive regulation here

Read our interviews with experts on malaria prevention here

_________

References:

Connolly, J. B., Mumford, J. D., Fuchs, S., Turner, G., Beech, C., North, A. R., & Burt, A. (2021). Systematic identification of plausible pathways to potential harm via problem formulation for investigational releases of a population suppression gene drive to control the human malaria vector Anopheles gambiae in West Africa. Malaria Journal 2021 20:1, 20(1), 1–69. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12936-021-03674-6

Czechowski, T., Rinaldi, M. A., Famodimu, M. T., Van Veelen, M., Larson, T. R., Winzer, T., … Graham, I. A. (2019). Flavonoid Versus Artemisinin Anti-malarial Activity in Artemisia annua Whole-Leaf Extracts. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10, 984. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2019.00984/BIBTEX

ENSSER, VDW, & Critical Scientists Switzerland (CSS). (2019). Gene Drives. A report on their science, applications, social aspects, ethics and regulations. Retrieved from https://ensser.org/publications/2019-publications/gene-drives-a-report-on-their-science-applications-social-aspects-ethics-and-regulations/

Guidance on the environmental risk assessment of genetically modified animals. (2013). EFSA Journal, 11(5). https://doi.org/10.2903/J.EFSA.2013.3200

Landier, J., Parker, D. M., Thu, A. M., Carrara, V. I., Lwin, K. M., Bonnington, C. A., … Nosten, F. H. (2016). The role of early detection and treatment in malaria elimination. Malaria Journal, 15(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12936-016-1399-Y/TABLES/1

Laurens, M. B. (2020). RTS,S/AS01 vaccine (MosquirixTM): an overview. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 16(3), 480. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1669415

Malariaprophylaxe und Empfehlungen des Ständigen Ausschusses Reisemedizin (StAR) der DTG. (2021, August). Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://www.dtg.org/images/Startseite-Download-Box/2021_DTG_Empfehlungen_Malaria.pdf

Maskin, E., Monga, C., Thuilliez, J., & Berthélemy, J. C. (2019). The economics of malaria control in an age of declining aid. Nature Communications 2019 10:1, 10(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09991-4

Okumu, F. O., Govella, N. J., Moore, S. J., Chitnis, N., & Killeen, G. F. (2010). Potential Benefits, Limitations and Target Product-Profiles of Odor-Baited Mosquito Traps for Malaria Control in Africa. PLOS ONE, 5(7), e11573. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0011573

Prüss-Ustün, A., Wolf, J., Bartram, J., Clasen, T., Cumming, O., Freeman, M. C., … Johnston, R. (2019). Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene for selected adverse health outcomes: An updated analysis with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 222(5), 765–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHEH.2019.05.004

Q&A on RTS,S malaria vaccine. (n.d.). Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/q-a-on-rts-s-malaria-vaccine

Target Malaria. (n.d.). The Science: What is gene drive? Retrieved from www.targetmalaria.org/ourwork

Target Malaria | Together we can end malaria. (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://targetmalaria.org/

The Nobel Prize | Women who changed science | Tu Youyou. (n.d.). Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.nobelprize.org/womenwhochangedscience/stories/tu-youyou

WHO. (2019). The use of non-pharmaceutical forms of Artemisia. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news/item/10-10-2019-the-use-of-non-pharmaceutical-forms-of-artemisia

WHO. (2022). Countries and territories certified malaria-free by WHO. Retrieved April 18, 2022, from https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/elimination/countries-and-territories-certified-malaria-free-by-who?msclkid=949a737cbf0711ec9474c0ab673942f3

Yang, D., He, Y., Wu, B., Deng, Y., Li, M., Yang, Q., … Liu, Y. (2020). Drinking water and sanitation conditions are associated with the risk of malaria among children under five years old in sub-Saharan Africa: A logistic regression model analysis of national survey data. Journal of Advanced Research, 21, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JARE.2019.09.001

Yasri, S., & Wiwanitkit, V. (2021). Artemisinin resistance: an important emerging clinical problem in tropical medicine. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Pharmacology, 13(6), 152. Retrieved from /pmc/articles/PMC8784654/